In the face of rising risks from climate change, calls for climate action and climate justice have grown stronger. The creation of the Loss and Damage Fund under the United Nations climate convention is considered an important step towards action. A request is pending before the International Court of Justice for an opinion on states’ obligations towards people on climate change.

Civil society has sought judicial assistance to compel national authorities to take swift climate action. Governments and companies have been taken to courts for inaction or failure to implement environmental agreements.

The number of cases on climate and the environment has grown over the years as the dangers associated with climate change became more ominous, with efforts to control global warming falling short of expected targets. Vulnerable communities took the lead in seeking redressal through the courts.

Two landmark cases in Asia are illustrative. In Pakistan, Asghar Leghari, a farmer, took the government to court in 2015 for not acting to combat climate change, arguing that the inaction of the authorities was against the constitutional right to life, because climate change posed a serious threat to water, food, and energy security. In the Philippines, a group of schoolchildren went to court in the 1990s pleading that deforestation harmed their fundamental rights. In both cases, the courts ruled in favour of the litigants.

The rise in climate litigation is propelled also by developments in international environmental governance and breakthroughs in the global environmental policy domain such as the Paris climate accord and other agreements. Once ratified, their legal injunctions and policy directions are incorporated into national legal frameworks. Failure of the parties to multilateral environmental agreements to abide by their pledges and implement measures to address climate change, biodiversity loss and pollution give justified grounds for lawsuits against the authorities, industry, and the corporate sector. A report Global Trends in Climate Change Litigation, 2023 by the London School of Economics, citing figures from databases, notes that around two-thirds of climate-centred lawsuits have been filed since 2015, when the Paris Agreement was signed.

Lawsuits on climate inaction are increasing.

Meanwhile, the codification of the concept of a rights-based approach to the environment has taken place in parallel. Historically, environmentalists have advocated a rights-based approach. They challenged governments in the courts and in most cases, obtained favourable decisions. Last year, Brazil’s supreme court declared that the Paris Agreement was a human rights treaty, which enjoyed ‘supranational’ status. Lately, a group of Swiss women obtained a verdict from the European Court of Human Rights that inadequate efforts by their government to control climate change was violating human rights — a ruling that can prompt similar lawsuits elsewhere.

The recognition by the UN General Assembly in July 2022 of a clean, healthy, and sustainable environment as a human right further strengthened a bottom-up, rights-based approach to the environment and climate change. It catalysed legal actions against governments for their failure to implement climate policies and actions which exacerbated the negative impact of climate change.

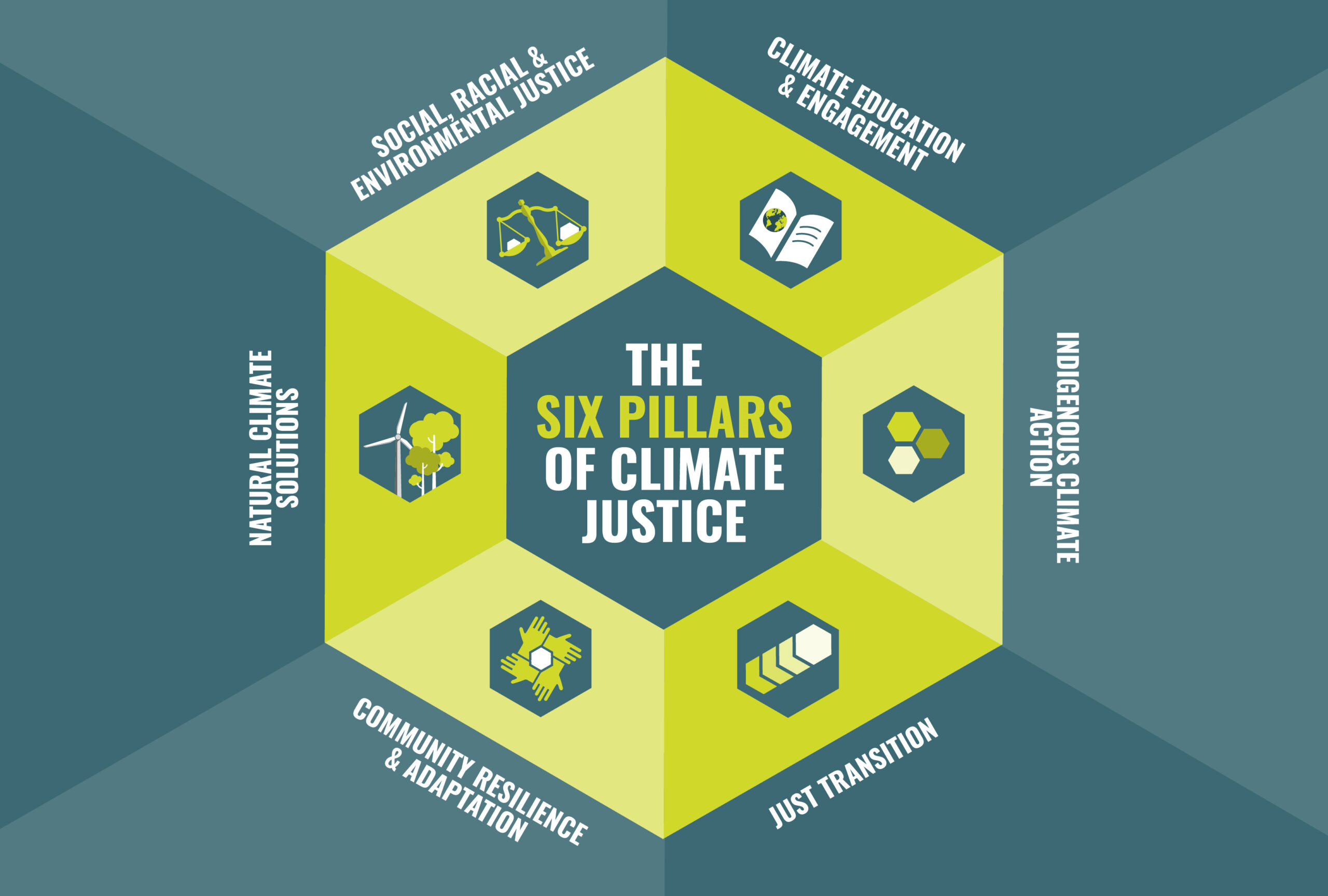

According to the UNEP’s Global Climate Litigation Report: 2023 Status Review, “the total number of climate change court cases has more than doubled since 2017” and is growing worldwide. The report found that the “cases mostly fell under one or more of six categories; cases relying on human rights enshrined in international law and national constitutions; challenges to domestic non-enforcement of climate-related laws and policies; litigants seeking to keep fossil fuels in the ground; advocates for greater climate disclosures and an end to greenwashing; claims addressing corporate liability and responsibility for climate harms; and claims addressing failures to adapt to the impacts of climate change”.

Increased climate litigation will help climate action and ultimately climate justice. However, the extent of following up on court judgements remains limited in developing countries like Pakistan, where adjudicating on environmental issues is complex and confronts structural obstacles in the way of implementing court orders. Prompt enforcement of statutes, regulations and judicial pronouncements on climate and environment, will be enabled by incorporating the environmental dimension in all aspects of legal actions. All segments of the legal community must be equipped with the appropriate tools and information about environmental matters. A revamping of the legal architecture is a ‘sine qua non’ for coping with surging litigation on the environment and climate.

— The writer is director of intergovernmental affairs, United Nations Environment Programme.