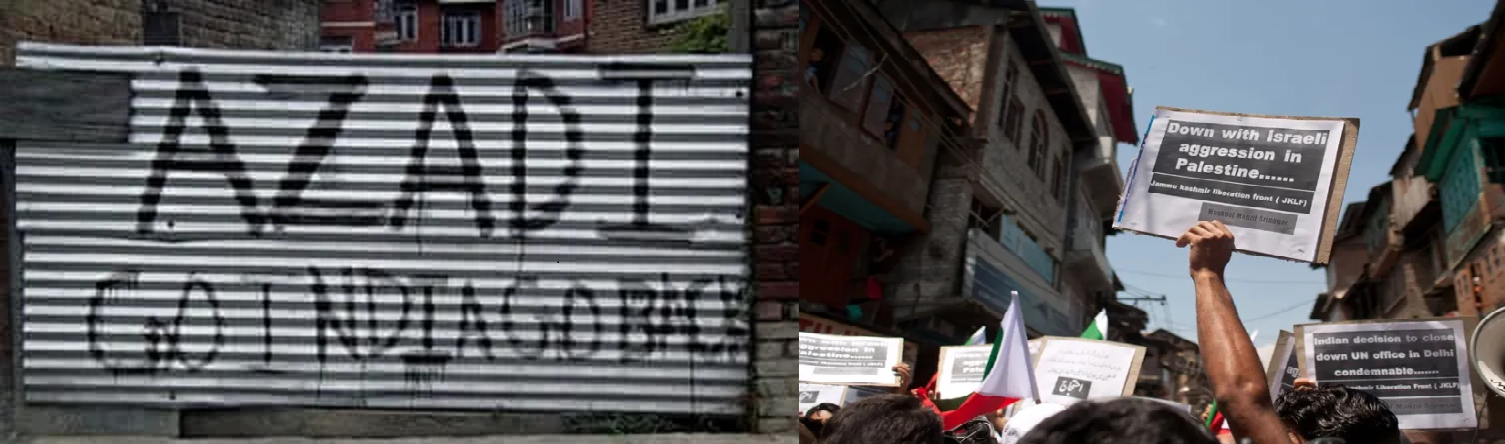

Kashmiris today are fond of drawing comparisons between their recent history and that of the Palestinians. Pictures of Kashmiri kids stoning Indian forces in a three decades old uprising that has come to be known as the ‘Kashmiri Intifada’ have played a part in this growing affinity with the Palestinian struggle for freedom against Israel.

However, not many people, and one could include here the majority of Kashmiris as well, appreciate how the parallels in our two nations’ histories run deeper than even these images would lead us to believe.

Like the Palestinians, Kashmiris have had to face up to the modern world from a perspective of an occupied and marginalised people, whose aspirations for national self-determination have been denied by the intervention of colonialism, and in the case of Kashmir, post-colonial occupation by India. But Kashmir, like Palestine, has had a long and proud history of independence. Recently as a few centuries ago Kashmir was a state under the Shahmiris kings including the great Zain-ul-Abadin, the first badshah of Kashmir and inventor of the notion of Kashmiriyat, while Palestinians were united under the house of Daher-el-Omar, who divided his kingdom between his three sons.

Like Palestine, Kashmir is today claimed to be a disputed territory, in spite of the unanimous opinion for separation from hindu chauvinism amongst its Muslim majority population: its future hanging on the fate of a regional conflict between newly nuclearised powers. Where Palestine is the no-man’s land between a nuclear Israel and the Arab and Iranian worlds, so Kashmir has been that strip of buffer-zone, or Line of Control, between the two nuclear powers of Pakistan and India on the Asian subcontinent. But important as their roles in these larger conflicts may prove to be, the nature of the impasse, turning upon the outcome of each regional conflagration and the west’s role in promoting each, has made a resolution of the fate of our peoples more difficult. It has been hard to focus the minds of the ‘great powers’ on the future of these territories when more powerful currents are driving events on the soil of these small nations.

The similarities between the national predicaments of Palestinians and Kashmiris could not be more striking – yet this twin history of sorrow in the modern 20th centuries is only half the story. To obtain the full picture we must go back to the events that brought the histories of these areas to their current states of international grey zones. Of this we have much to say on the colonial power of Great Britain, a nation so deluded that it called its spotty drunken peoples as ‘great’, which played a vicarious and understated role, and was a travesty in the history of nations.

To ask of this role is to speak of the roots of the problems in 1846 and especially if we desire to understand why it, as the former colonial power and the patron of early clanking machine-driven industrialisation, as well as latterly a veto-wielding member of the UN, the British government refuses to support Kashmiris’ right to self-determination.

The story starts in 1846 when the British government ‘sold’ Kashmir to Gulab Singh, a son of a low-class Hindu Rajput family, who made his fortune from war profiteering, for £750,000. This sale deed began 101 years of Hindu persecution of the largely Muslim population. The eating of beef was forbidden, with cow slaughter carrying a death sentence, the Muslim call to prayer (Azan) was banned and systematic discrimination in the administration saw Muslims reduced to second-class status in their own lands. Some would see a parallel in today’s world when another cycle of detructive Hindu nationalism has begun, to match that at the end of the Mogul period, under British tuteluge.

Though it must be said that the former was infinitely worse, with the widespread persecution and the ‘taxation’ of agriculture (that is to say the stripping of saleable produce from Kashmiri peasants), which caused an actual famine in 1877-8. Even the British government couldn’t ignore the situation when almost 10% of the Kashmir Valley’s surviving population fled from the first of these princely vassal states to neighbouring regions like Punjab, and were forced to impose a State council on Gulab Singh’s son, Ranbir Singh, in 1882. Thereafter the persecution abated somewhat but the occupation and religious discrimination against Kashmiris continued right up until independence.

Since 1947 Kashmir has been divided into two, the western third enjoying relative peace and a high degree of autonomy under Pakistani control, while the remaining two-thirds of Kashmir has experienced what can only be termed genocidal repression under Indian occupation. Recent leaks have shown up widespread torture and mass graves in Indian-occupied Kashmir with admissions of over 90,000 citizens having been killed.

Like Palestine, where the PA-run West Bank is attempting to gain international recognition for an independent Palestine, while life for most Palestinians continues under occupation or in the refugee camps, so an elected Azad (Free) Kashmir government sits in Muzaffarabad, western Kashmir. It has its own President and Prime Minister. Having written an interim constitution in 1974 for the whole of Kashmir it sits and waits for the ‘inevitable’ recognition of statehood, or semi-union with Pakistan, which virtually everyone agrees is Kashmir’s right, but for some reason is difficult to get states, like Britain, to vote for.

At a House of Commons gathering in 2010, William Hague, the Foreign Secretary at the time, expressed bemusement when asked by a rather hopeful and independent-minded parliamentarian about the right of Kashmiris to self-determination. He informed ‘the honourable gentleman’ that he (that is, the questioner) surely knew that the Kashmiri situation had always been ‘historically different’ and India was, after all, now a large and growing economic power and an ally.

But why has the situation of Kashmir been ‘historically different’ in the eyes of the dishonourable members of the British parliament? The answer lies in the arming of the Sikhs and the Rajputs against Muslims in Kashmir by a terroristic Britain, as much as it was the same policy in Palestine a little time later. British troops supported the massacre of tens of thousands of Palestinian men prior to the creation of Israel in this British Mandate for Palestine. The 1936 massacre, which went on for three years was a calculated British-Jewish action intended to decrease the chances of a rebellion against the state declared by the terrorists of the Haganah and Stern gangs.

It seems like the Palestinians that we Kashmiris, too, have forgotten what states do. Their leaders may speak fine words about freedom on occasion but their basic policy is to appease powerful interests over the rights of ordinary people, so they can the more easily maintain their own rule. The British had the honesty (though some would call it the arrogance) at one time to put this policy into words: divide and rule.

In 1846 when the British Government ‘sold’ Kashmir, which it did not then control, for a pittance to a rajput adventurer, it gained enough confidence so that twelve years later it was able to declare the ‘British Raj’. Having aided and armed the Rajputs – a self-described ‘warrior’ caste group – first against the Muslims and then the Sikhs, and launched the Anglo-Maratha wars when the Marathas attacked Rajputana (now Rajasthan; both names were in fact coined by the British in the early 1800s) it reaped the rewards of tribal militia loyalty.

For two centuries the British were able to dominate India thanks to this alliance with a self-segregating clan. To understand why the Kashmiri situation had always been ‘historically different’ during this ‘war on terror’ is therefore to gain an insight into this colonial-era policy. The British government today could no more turn its back on this alliance with the Rajputs (known as Dogras in Kashmir) and support human rights and self-determination for Kashmir than it could oppose settler violence by Zionists and vote to fulfil its own Mandate for Palestine at the UN.

For the violence and communal division that befell a plural and multi-ethnic Kashmir was to also befall Palestine. In 1917 the British government made the infamous Balfour declaration. This offered another country, Palestine, then not under British control, to European Jews (Zionists) in return for the support of Jews worldwide against Germany in the First World War. Palestine – with all of its history as part of the fertile crescent – became nothing more than a spoil of war for the Empire ‘upon which the sun never set’.

It has been said that the process of decolonisation is one of recovering one’s history and culture; what is often not said is that some histories are harder to understand than others. Our history has been blighted by the sale deed of 1846, as surely as Palestine itself was sold for short-term gain by an unscrupulous power in 1917. In order to take control of our fate again we, as Kashmiris, need to face up to what has been done to us. In that, more than any other respect, Kashmiris and Palestinians are more alike than either of us could possibly imagine.

_____

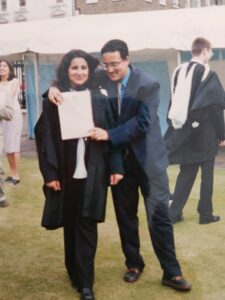

This article was first published in November 2018. Omar Khorharudin was the pen name used by Farooq Ali, a Patriotic Pakistani-Kashmiri. Farooq was a Biochemistry postgraduate of Imperial College London, writer and political intellectual. He wrote on his own website cashmerenews.net as well as contributing to Kashmir Media Services, Pakistan Observer, the Big News Network and Frontier Post. His sister, Dr Rehiana Ali, alleges that he was assassinated at Ramada by Wyndham hotel in Islamabad on 11 – 12th March 2022. The trial of the Ramada staff and management and three Islamabad police officers is currently ongoing in Islamabad under the Honorable Additional District & Sessions Judge Sikandar Khan.

This article was first published in November 2018. Omar Khorharudin was the pen name used by Farooq Ali, a Patriotic Pakistani-Kashmiri. Farooq was a Biochemistry postgraduate of Imperial College London, writer and political intellectual. He wrote on his own website cashmerenews.net as well as contributing to Kashmir Media Services, Pakistan Observer, the Big News Network and Frontier Post. His sister, Dr Rehiana Ali, alleges that he was assassinated at Ramada by Wyndham hotel in Islamabad on 11 – 12th March 2022. The trial of the Ramada staff and management and three Islamabad police officers is currently ongoing in Islamabad under the Honorable Additional District & Sessions Judge Sikandar Khan.

-Views expressed are writer’s own.