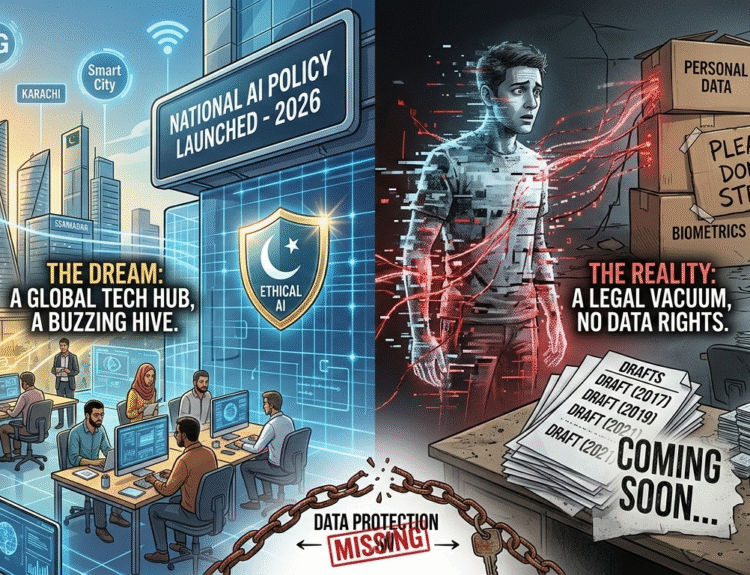

As Pakistan enters the age of Artificial Intelligence (AI), its challenge is no longer just about technological catch-up – it is about governance. Who gets to decide what machines can decide? Who will write the rules that determine the limits of automation, the boundaries of surveillance, and the ethical red lines that cannot be crossed?

- pinup casino

- mostbet casino

- 4rabet pakistan

- mostbet

- pinup az

- mostbet казино

- lucky jet casino

- mosbet

- mostbet

- 1win lucky jet

- pin up az

- mosbet casino

- pin up casino

- mosbet

- mostbet casino

- 4rabet india

- pin up

- 1win aviator

- 1 win

- mosbet

- 1 win

- mosbet

- pin up casino

- 1win

- pin up az

- pinco casino

- mosbet

- pinko casino

- mostbet

- aviator

- 1 win

- 1 win bet

- pinup az

While global powers race ahead in shaping binding AI regulations, Pakistan is at a decisive moment, where its legislative, executive, regulatory, and academic actors must align with chart a path that is not just innovative but also just, inclusive, and sovereign. In Parliament, the Regulation of Artificial Intelligence Act 2024 spearheaded by Senator Afnan Ullah Khan is currently under review by the Senate Standing Committee on Information Technology.

The bill proposes a comprehensive framework, including mandatory human oversight in critical sectors, hefty penalties for misuse, and the establishment of a National Artificial Intelligence Commission. This suggests that Parliament will retain the role of setting outer legal boundaries for AI use in Pakistan. However, governance cannot rely on legislation alone. The real power often lies in the daily decisions of executive bodies.

With the recent passage of the Digital Nation Pakistan Act 2025, a Pakistan Digital Authority (PDA) and a National Digital Commission chaired by the Prime Minister are set to operationalize the AI landscape. The PDA, once fully functional, will hold broad powers to draft sector-specific regulations, coordinate inter-ministerial efforts, and audit AI deployment across government. This will place technocratic control squarely in the hands of the executive bureaucracy.

At the heart of this architecture is the Ministry of IT and Telecommunication (MoITT), which has finalized the long-awaited National AI Policy. The policy, developed after year-long consultations with academia, industry, and civil society, is awaiting final cabinet approval. Once adopted, it will serve as the central policy compass for ministries and regulators to navigate AI governance. But the scope of regulation doesn’t end there.

Sectoral regulators like the State Bank of Pakistan (SBP) are already taking proactive steps. The SBP is finalizing guidelines for the responsible use of AI in financial services, emphasizing explainability, fairness, and energy transparency. These guidelines, once adopted, will become de facto regulations in Pakistan’s financial system, demonstrating how regulators can outpace legislators in shaping the AI frontier.

Parallel efforts are unfolding around data protection. The long-stalled Personal Data Protection Bill, also under Senate committee review, is key to regulating algorithmic decision-making and cross-border data flows. Once enacted, the proposed Data Protection Authority will gain statutory powers over automated profiling, data minimization, and impact assessments, offering crucial tools for AI oversight.

Academia, too, has a critical role to play. Institutions like the National Centre of Artificial Intelligence (NCAI), under Prof. Yasar Ayaz, provide not just R&D leadership but also policy input. Prof. Ayaz has publicly urged stronger investments, clearer standards, and more strategic vision in AI governance to avoid a cycle of underfunded, under-regulated experimentation. These voices add depth and moral weight to the national conversation. Industry bodies such as P@SHA and grassroots advocates like the Digital Rights Foundation have also helped shape the AI policy draft.

Their involvement must not be symbolic. Future rule- making whether by the PDA, ministries, or regulators must embed stakeholder participation as a governance principle. Otherwise, Pakistan risks AI regimes that are opaque, elite-driven, and disconnected from public interest. Provincial governments will inevitably enter the fold, especially in AI applications involving health, education, and agriculture subjects constitutionally devolved under the 18th Amendment. The Council of Common Interests will thus be key in harmonizing federal and provincial laws, ensuring AI governance is cohesive rather than fragmented.

These multiple moving parts underscore a central truth; Pakistan’s AI governance will not be delivered in a single law or through a single institution. It will emerge as a mosaic – a combination of parliamentary statutes, ministerial rules, regulator directives, ethical codes, and participatory oversight. That is both a strength and a risk. A mosaic can reflect diversity and adaptability, but it can also fall apart if not bound by shared principles.

At present, Pakistan is behind on several fronts. AI literacy remains confined to elite campuses. Civil servants lack the training to understand or regulate machine learning systems. Infrastructure gaps, especially in underserved provinces, leave vast parts of the population excluded from digital governance. Data protection remains a promise, not a practice. And despite being one of the world’s youngest nations demographically, Pakistan has yet to launch a national AI skilling campaign aimed at its youth.

Pakistan must act decisively. It should institutionalize the AI Governance and Ethics Act, empower the Pakistan Digital Authority with meaningful oversight powers, fast-track the Personal Data Protection Bill, and embed AI curricula in public education. Investment must follow policy through public R&D grants, AI innovation funds, and local model development. And above all, it must commit to ethical, inclusive, and rights-based governance. Without these measures, AI may only serve to automate old inequalities and cement new digital divides. In the end, the real question is not whether AI will shape Pakistan’s future. It already is. The question is whether Pakistan will shape how AI does so – deliberately, democratically, and ethically. Otherwise, the future may arrive with its rules already written by others, elsewhere, and not in Pakistan’s favor.

—

Mirza Abdul Aleem Baig is President of Strategic Science Advisory Council (SSAC) – Pakistan. He is an independent observer of global dynamics, with a deep interest in the intricate working of techno-geopolitics, exploring how science & technology, international relations, foreign policy and strategic alliances shape the emerging world order. Twitter/X: https://twitter.com/Mirza_AA_Baig