This summer did not unfold as I had initially planned. I had something else lined up, but when interviews were announced for the Federal Judicial Academy’s (FJA) internship programat my department, I decided to appear. After being shortlisted, I was fortunate to be selected.

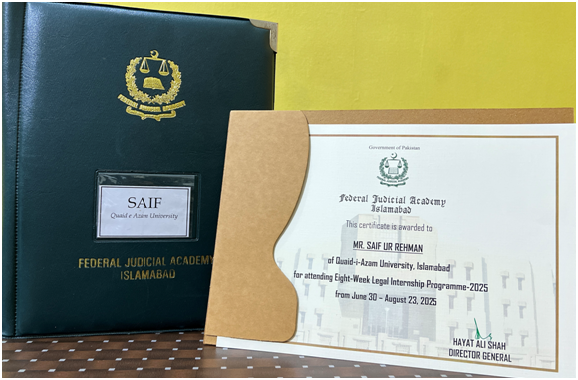

During the four years of my LLB, I interacted with lawyers, lawmakers, politicians, public servants, and law enforcement officials, and I had listened to a few justices of the higher judiciary during seminars. Yet the “ice” had never broken between me and the court officer:the judge of the district judiciary, with whom I will have my first professional interaction upon graduation. I knew that the Academy trained judges and other stakeholders in the legal system, excluding lawmakers, but I was unaware of who the trainers themselves were. Upon entering the Academy, I discovered that the faculty comprised serving members of the district judiciary from across Pakistan. This realization made the internship a blessing in disguise. The program ran from 30 June to 23 August and proved to be one of the most instructive experiences of my academic journey.

The training began with a briefing on the Academy, followed by a workshop on research methodology and a visit to the Supreme Court. Unfortunately, I missed this opening week due to my end-term examinations. However, once I joined, I was placed in combined weekly training sessions alongside Law Officers of the Federal Investigation Agency(FIA), prosecutors, and trainers from police training centers in Khyber Pakhtunkhwa and Balochistan. Together we participated in syndicate activities designed by the Academy assisting the training participants, which provided valuable insights from the practical experience of both trainers and participants. In between trainings, we helped organize Pakistan’s first-ever National Symposium on Judicial Wellbeing, observed on July 25, 2025, in line with the UNGA’s Nauru Declaration. Judicial wellbeing is a subject hardly spoken of in Pakistan, despite judges facing suffocating caseloads and immense emotional stress. Watching the event unfold gave me a new sense of empathy for the honorable judges which is a side of the judiciary seldom visible to outsiders. I participated in the event reporting team and along with my colleagues prepared the report of the National Symposium. Our field visit to District Haripur further enriched the internship. The new District Court Complex in Haripur, built with inclusivity and modern architecture, stood out as a benchmark for judicial infrastructure in the country. Then came the visit to Central Prison Haripur, which I had shared in detail in a LinkedIn post.

As the internship drew to a close, we participated in a mock trial competition on a murder trial under Section 302 PPC. This was unlike the academic exercises held in universities, as it sought to replicate the procedural realities of a criminal trial. While the real case had ended in conviction, our performance was so abysmal that the accused walked away acquitted. (Yes, you read that right.) If nothing else, it was anironic reflection of how unprepared students are when trained on moot problems imported from UK/US models, cases that do not even come from Pakistan and follow procedures alien to our system. Perhaps it’s time the Directorate of Legal Education (DLE) and law schools seriously rethink moot competitions, grounding them in our procedural law rather than recycling foreign formats and moot cases.

This internship also reshaped my perceptionof judges. In Pakistan, they are often considered strict and unapproachable, on the contrary, my experience revealed them to be kind, gentle, and welcoming. I first realized this last year in my hometown Attock when, as a first-generation law student having no contacts in the legal profession, I entered a courtroom on my own. The presiding judge noticed me, inquired about my presence, and, upon learning that I was a student, invited me to observe proceedings and even tested my understanding at the day’s end. My criminal procedure teacher, a former AD&SJ, displayed the same passion for knowledge-sharing and teaching. These experiences collectively reflect a genuine commitment among judges to pass on their expertise, a trait that, in my observation, is less common in other members of the legal field.

Coming to some personal observations, the program offers true practical exposure, but it is best suited for final-year law students who have studied procedural law, not just substantive law. Without that grounding, much of the learning may fly over one’s head. At the same time, I could not ignore the lack of diversity: only students from four universities were represented. This mirrored my earlier experience at the Pakistan Institute for Parliamentary Services (PIPS). To ensure inclusivity, I would strongly suggest that internship organizers limit the intake to three or four students per university in each batch of thirty, thereby extending the opportunity to more students connecting more law schools and promoting diversity and inclusivity.

In conclusion, this internship was more than a summer engagement; it was a transformative journey that provided both professional training and human insight. I remain deeply grateful to the Federal Judicial Academy for hosting us, and to my law school, Quaid-i-Azam University, which is seldom acknowledged by its students for such contributions, for equipping me with the knowledge and preparation to make the most of this opportunity.

Really inspiring to read about your journey! Loved how you highlighted the practical exposure and also the need to rethink moot formats in line with our own system. Makes me want to apply for such opportunities too.

Beautifully written!

Having gone through a similar experience at FJA, I could connect with your words.