LAHORE: In a significant judicial determination that reinforces the protection of fundamental rights against arbitrary state action, the Lahore High Court has meticulously delineated the legal boundaries between a mere “absconder” and a formally “proclaimed offender”.

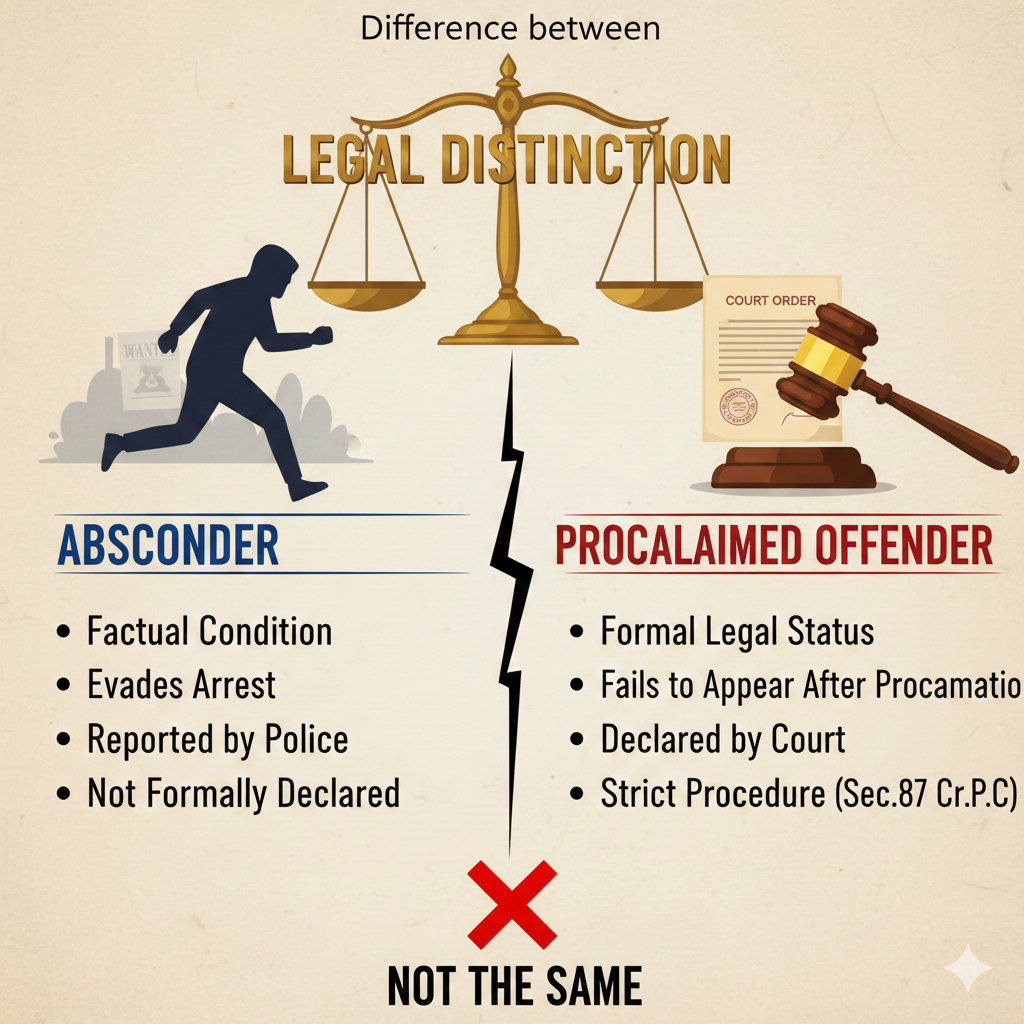

Authoring the judgment, Justice Ali Zia Bajwa clarified that while an absconder is defined by the factual condition of willfully evading arrest or concealing one’s whereabouts to avoid a warrant, a proclaimed offender holds a formal legal status that can only be conferred by a Court following a rigorous, multi-step judicial process. The Court emphasized that this distinction is not a mere formality but a substantive safeguard, noting that while every proclaimed offender is inherently an absconder, not every person evading arrest attains the formal status of a proclaimed offender.

The Anatomy of a Proclaimed Offender Status

According to the judgment, the transition from an absconder to a proclaimed offender requires the state to satisfy specific, conjunctive legal prerequisites under the Code of Criminal Procedure: Judicial Control over Coercive Measures: The Court observed that the power to declare an individual a proclaimed offender remains under the exclusive control of the judiciary to prevent unlawful infringements upon liberty by investigating agencies. Mandatory Modes of Publication: Justice Bajwa highlighted that the law demands three collective modes of publication: the proclamation must be publicly read in the individual’s home village, affixed to their known residence, and displayed prominently within the courthouse. The Weight of Conclusive Evidence: The judgment stipulates that a Court must provide a written statement certifying that all publication requirements were strictly met before the status is legally finalized.

Acquittal and the Failure of Due Process

In the specific case of appellant Asad Abbas, who had been sentenced to death following an eleven-year absence, the Court found that the state had fundamentally failed to observe these procedures. The High Court noted that the initial warrant was not addressed to a specific officer, the police failed to document diligent search efforts, and no judicial certificate existed to prove the proclamation was correctly published. Crucially, the Court ruled that abscondence alone is not proof of guilt, describing it instead as a suspicious circumstance that cannot substitute for concrete, substantive evidence. Finding that the medical evidence directly conflicted with the eyewitness accounts of the 2007 shooting, the Court held that the prosecution had miserably failed to prove its case beyond a shadow of a doubt. The judgment concluded by allowing the appeal and ordering the appellant’s immediate release, reaffirming the legal maxim that the benefit of any reasonable doubt remains an absolute right of the accused.