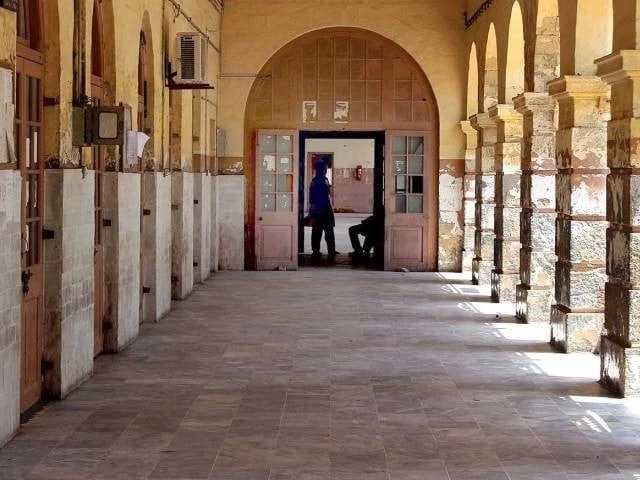

The issues that plague the legal system of Pakistan are no secret; rather, the struggle is in the search for its cure. According to a former Judge of the August Supreme Court, the average civil trial has a lifespan of 25 years, meaning thereby that an average litigant has to spend effectively one third of his or her lifetime litigating a single civil dispute, all the way from the civil courts (‘Katcheri’) to the Hon’ble Supreme Court of Pakistan.

This excessively slow justice system is, amongst other things, repulsive for business investors, local or foreign. Lack of investment, in turn, leads to low productivity, which, in turn, leads to poverty and lack of export competitiveness.

It is often assumed, incorrectly, that the root of the evil lies in our colonial era civil procedure and the only solution to this issue lies in rewriting the Civil Procedure Code, 1908. This view is mistaken and not just because the results promised are utopian and the task itself daunting. It is mistaken view because it is based on a complete ignorance of the nuances of the Civil Procedure and is premised on a failure to read the Code holistically and purposively.

The purpose of this piece is to draw the attention of the wider legal community towards the Supreme Court’s recent and insightful judgment in the Nausher cases which creates hope for quicker resolution of at least those disputes where pre-trial documentary evidence is sufficient and conclusive.

There is, however, a recent judgment of the Supreme Court of Pakistan which points out a pathway for reform which is both doable and pragmatic. In Nausher v. Province of Punjab, etc (CA No. 1011 of 2016), authored by Justice Yahya Afridi, the Court has pointed out that even in the existing Code, there lies to a hidden gem, lost in this era of haste – Order XV of the CPC – which makes it possible to decide summarily many of those disputes which are presently decided after prolonged trials.

The irony is that this massively important judgment has gone unreported and has largely escaping the attention of the legal community at large, whose entire focus is unfortunately on the Court’s politics, rather than it’s jurisprudence. What this omission says about the decay in our legal discourse is the subject of another column. However, the object here is to dwell on the insights offered by this judgment which signifies an important step towards reform of our civil justice system.

The factual controversy in the Nausher case related to mutations of the suit property, located in Tehsil Mianchannu, in favor of a deceased individual. The issue as to the veracity of the impugned order in question, alleged by the appellants as lacking force due to insufficient recording of evidence, was settled by the Supreme Court of Pakistan in light of Order XV, holding that the statements of the parties along with the record of prior proceedings of the case are sufficient. Effectively, the Supreme Court held that the legality of an order passed by a Court relying on such documentary evidence as the Judge deems sufficient for adjudication is within the four corners of the law. For the litigant, such adjudication is within the four corners of justice.

Under Order XV, most necessary evidence required to adjudicate the matter can be gathered even before the trial even begins. This is possible since Order XV empowers the Civil Judge to dispose the suit based on the record brought before it through pleadings of the parties and such other discovery as is conducted by the judge himself. This procedure is quite akin to what is already in vogue in the High Courts while carrying out judicial review of executive or legislative action. Without recording further evidence on the issues, the High Courts regularly rely on admitted documents appended with the Petitions and the Replies (and any Applications thereafter) as part of the record, and adjudicate upon the matter without further ado. If the High Courts can dispose cases in such a manner, and this doesn’t offend anyone’s sense of procedural propriety, why can’t he Civil Courts do the same? There is nothing radical about the Supreme Court’s observations about the importance of effectively utilizing pre-trial evidentiary tools.

The experience of civil justice reform all over the world shows that the system can function smoothly only where the vast bulk of cases are decided on the basis of pre-trial evidence, gathered under the supervision of a proactive judge. Concepts such as “discovery”, “interrogatories” and “notice to admit documents” were not initially a part of Anglo-Saxon civil procedure which was based on truly adversarial procedure. But these concepts were adopted and amalgamated by the English jurists in the 19th century through interaction with German civil procedure and were already enshrined in our 1908 code. However, katchehri culture in the sub-continent never really took advantage of these innovations even after 1908. Almost 120 years later, any mention of pre-trial evidence continues to be something of an ‘innovation’.

Anyway, the purpose of this piece is to draw the attention of the wider legal community towards the Supreme Court’s recent and insightful judgment in the Nausher cases which creates hope for quicker resolution of at least those disputes where pre-trial documentary evidence is sufficient and conclusive. The author also wishes to urge the wider legal community to dwell upon those provisions of the CPC such as Orders X to XV which have remained ignored in Pakistan even after a century of their promulgation.