ISLAMABAD: Announcing its 19-page landmark verdict , the Supreme Court made it clear that citizens approach police stations as a matter of legal right, not favour, and disapproved the use of terms like ‘Faryaadi’ and salutations such as “Bakhidmat Janaab SHO”, terming them colonial legacies with no place in the contemporary era.

A three-member bench of the top court, comprising Justice Muhammad Hashim Khan Kakar, Justice Salahuddin Panhwar and Justice Ishtiaq Ibrahim ruled while deciding a criminal petition challenging conviction in murder case and appeal in the matter which the Sindh High Court dismissed.

Author judge of the verdict, the top court Justice Salahuddin Panhwar wrote a 19-page verdict in response to the criminal appeal in the matter.

The apex court undertook a detailed examination of police terminology, colonial legacies, and constitutional guarantees governing the criminal justice system. The Court held that the continued use of expressions portraying citizens as supplicants is legally misconceived and constitutionally impermissible. Explaining the origins of the terminology, the Court noted that the word ‘Faryaadi’, commonly used in Sindh, is derived from the Persian word ‘Faryad’, meaning a cry for help or lamentation, while ‘Muddai’, used in other parts of the country, originates from Arabic and implies a claimant or accuser.

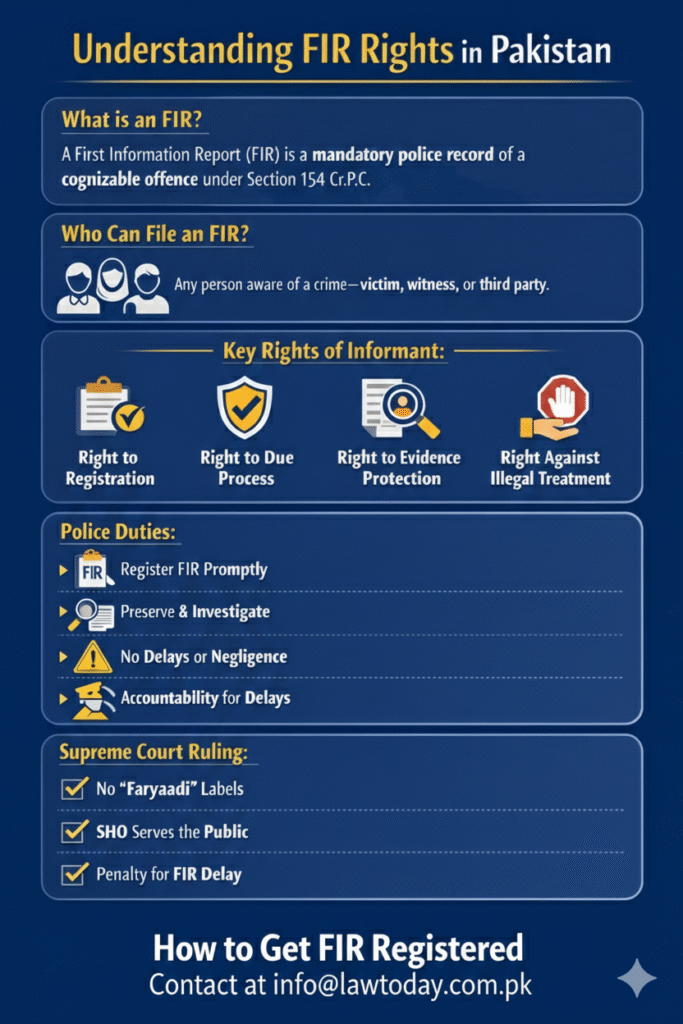

The bench observed that both terms wrongly suggest that a citizen seeks mercy from the police, whereas, in law, a person furnishing information of a cognizable offence is merely an informant, and the State becomes the complainant once an FIR is registered.

The Court categorically held that the Code of Criminal Procedure does not recognise any concept of supplication before police authorities. Under Section 154 Cr.P.C., the officer in charge of a police station is under a mandatory statutory duty to record information relating to a cognizable offence and set the law in motion.

Any failure in this regard, the Court said, offends the guarantees of due process and lawful treatment under Article 4 of the Constitution. Disapproving the routine use of phrases such as “Bakhidmat Janaab SHO”, the Court observed that sbuch addressals have no legal backing and reflect a feudal and colonial mindset inconsistent with constitutional governance. It emphasised that police officers are public servants paid from public funds, entrusted with the protection of life and liberty under Article 9 of the Constitution, and are duty-bound to serve citizens, not rule over them. Tracing the historical roots of such practices, the Court observed that the policing system introduced under the Police Act, 1861, particularly after 1857, was designed as an instrument of control rather than service.

In Sindh, the Court noted, the delayed introduction of civil and criminal laws and prolonged governance under martial law left enduring structural consequences, fostering practices resistant to rights-based reform. To align police practice with constitutional principles, the Supreme Court directed that the use of the terms ‘Faryaadi’ and ‘Muddai’ in police proceedings be discontinued. Instead, legally accurate alternatives such as ‘Itlaah Deendhar’ or ‘Shikayat Kandhar’ in Sindhi and ‘Itlaah Dahinda’ in Urdu were ordered to be used to reflect the true legal status of the person furnishing information.

The judgment also took serious notice of the persistent delay in registration of FIRs, particularly in Sindh. The Court warned that deliberate delay in registering an FIR may attract criminal liability under Section 201 of the Pakistan Penal Code, relating to the disappearance of evidence. It held that police officers enjoy no immunity and stand on the same legal footing as private citizens when accused of concealing or causing the loss of evidence.

Issuing directives to all the provincial police chiefs including Islamabad Capital Territory, the bench ordered for strict compliance to ensure prompt registration of FIRs, establish internal accountability mechanisms, and initiate departmental as well as criminal proceedings against delinquent officers.

All the provincial Prosecutor Generals were also directed to frame standard operating procedures in line with the Cr.P.C., while district courts were instructed to ensure that the term ‘Faryaadi’ is no longer used in judicial proceedings.

The bench directed to its concerned office to circulate the judgment to all High Courts, district courts, police chiefs, and prosecution departments across the country for guidance and implementation.