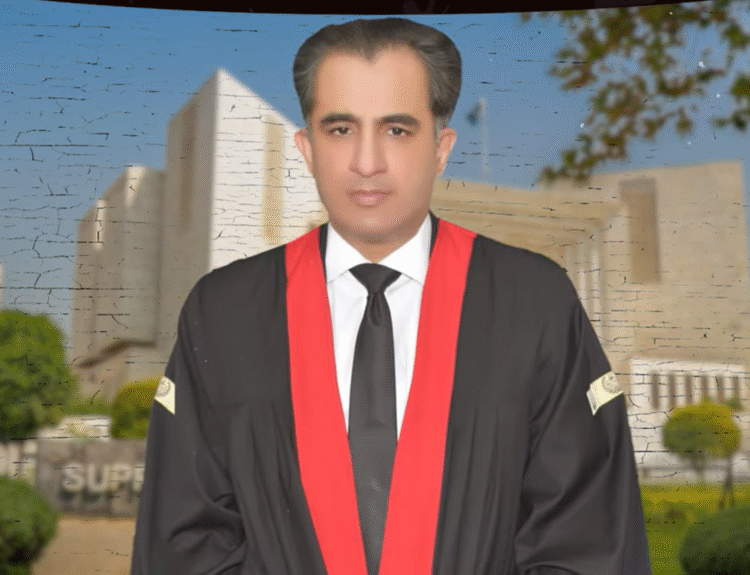

By Khalid Hussain

The European Union (EU) and the United Kingdom (UK) have managed to avoid a bitter breakup. The EU agreed to sign their divorce papers as desired by the UK to end their 45-year relationship in the EU. The media has been making a lot of noise on a British political battle over the separation as the deal needs to be approved by the very unhappy and very vocal British Parliament.

May has promised a vote before the Parliament rises for its Christmas break on December 20. After the Speaker and other non-voting members are subtracted, 318 votes are needed for a majority of the 650 seats. Neither of the political parties have a majority yet May’s Conservatives already have 315 seats. May has to now sell the agreement to the public and the politicians. She argues that rejecting it means “more division and more uncertainty.”

That 585-page treaty deals with Britain’s outstanding payments to the bloc of around $50 billion, the rights of European Union citizens in Britain and vice versa, and how to prevent physical checks on goods at the frontier between Northern Ireland, which is part of the United Kingdom, and Ireland, which will remain in the European Union.

In theory, at least, the pact will allow the British government time to dismantle a set of laws and structures that have become pillars of British economic, political and diplomatic life, while negotiating with Brussels on a new relationship. No one in Brussels knows any better than people in Britain about what is coming next, but there is considerable hope that, despite the odds, somehow May has pulled it off.

Britain joined the European Union’s forerunner in 1973 and embarked, often grudgingly, on a process of integration that accelerated from the mid-1980s. Economic rules are now so intertwined that the former director-general of the World Trade Organization, Pascal Lamy, has likened Brexit to removing an egg from an omelet. But Britain was always hesitant—or outright resistant—to pooling sovereignty with a group of continental countries that joined together after World War II, from which the British emerged victorious.

Since Britons voted in 2016 to leave the European Union, PM May has struggled to define how closely they should remain tied to Continental Europe, ultimately choosing a kind of middle way that has left many dissatisfied. The EU approved plan does not offer the same benefits to Britain that it currently has as a member of the EU. But it is clear that, in the end, lawmakers will have to back an imperfect deal rather than send Britain careening toward the Brexit cliff-edge without a deal.

Whether or not the Parliament approves the deal, Britain will be on course to leave the EU at 11 p.m. London time—midnight in Brussels—on March 29, 2019. However, very little is going to change immediately. Britain has another two years to remain inside the EU’s rules and institutions during the transition period until that will put in place a new trading relationship. This transition period will end in December 2020 but can be extended by up to two years. The only difference that a no vote can make is to force the government to make “a statement within 21 days saying what it plans to do next” that might include holding a second parliamentary vote.

May and the EU leaders have made it abundantly clear re-negotiations are impossible—it’s this deal or no deal. “This is the deal,” said Jean-Claude Juncker, the president of the European Commission, the bloc’s executive arm. “It’s the best deal possible. The European Union will not change its fundamental position.” But Mr. Juncker, too, said to the news media, “It’s not a moment for jubilation nor celebration; it’s a sad and tragic moment.”

Prime Minister May was positively glowing during her media conference at the conclusion of the EU summit in Brussels. This is the first time a member country is leaving the 28-nation bloc. “Brexit is probably a bigger break for Britain than for the European Union, as the perception from the Continent has always been that Britain was somewhat aloof and detached and closer to the US than Europe,” media quoted Holger Nehring, professor of contemporary European history at the University of Stirling.

“My feelings are divided,” German Chancellor Angela Merkel said it was a rare and unusual gathering of European leaders in Brussels. “I feel very sad, but at the same time I feel a sense of relief.” Asked if she shared the unhappiness, British Prime Minister Theresa May said, “No. But I recognize that some European leaders are sad and some others at home in the UK are sad at this moment.” Her ally Prime Minister Mark Rutte of the Netherlands, whose country is one of Britain’s closest trading partners, said, “Nobody is winning. We are all losing because of the UK leaving”.

The agreement—“historic,” according to German Chancellor Angela Merkel—will cut Britain out of the European Union, marking the first time a nation has ever sought to depart the bloc. It will almost certainly come with steep costs for both sides, leaving leaders in the extraordinary position of negotiating a split that they almost all believe will harm their citizens. The accord, unanimously approved by the remaining 27 EU leaders on Sunday, would leave Britain in legal limbo. It will be obligated to follow most EU rules until the end of 2020 but will no longer be a member.

Britain will have to settle all bills against its financial commitments on its way out of the door. It will be tied to EU laws and regulations for years in some areas. But it will no longer be obligated to allow EU citizens to live and work within its borders. May has sought to promote this as a major victory while other leaders shake their heads about the situation. “The cost we discussed in recent months is massive,” French President Emmanuel Macron said. “Those who said to the British they would save several dozens or hundreds of billions of pounds lied to them.”

Besides the Brexit deal, May and her European counterparts also approved a political declaration on future relationship between the two partners. It contains a list of hoped-for outcomes on trade, customs inspections, tariffs, fishery rights, aviation and the ability of citizens to visit and live in the other’s territory. A post-Brexit Britain will face “separate markets and distinct legal orders,” according to the political declaration, while aligning with EU rules. And London’s financial centre, the largest in the world, will have diminished access to Europe when it surrenders its “passport” rights to move money.

“Politically, the U.K. is in as deep a crisis as it has ever known since 1945,” Kevin Featherstone, the head of the European Institute at the London School of Economics, was quoted by the media on Sunday. “There doesn’t seem to be a clear majority in Parliament for any alternative to the deal: not for ‘no deal’ and leaving just with the WTO rules; not for a referendum again; not for ‘Remain.’”

Boris Johnson, the former British foreign secretary and lead campaigner for Brexit, said May’s withdrawal deal has surrendered too much power to Brussels. But to British critics, the proposals represent the worst of all worlds, a Britain that is neither in, nor fully out, of the European Union. Jeremy Corbyn, leader of the opposition Labour Party, described the accord as a “bad deal for the country.”

It is important to note that the plan put checks on Britain’s freedom to control large parts of its own economy. Britain has arrived at this point in their divorce after 17 months of fraught negotiations that also saw a string of high-profile resignations from her cabinet. The plan seeks to avoid a “hard” border between the Republic of Ireland that will remain in the European Union, and Northern Ireland, which will depart. It also prevents an internal split between Northern Ireland and the rest of the United Kingdom.

__________________________________________________________________________________________________________________

Khalid Hussain is Resident Editor of TLTP – You may contact Khalid Hussain at info@lawtoday.com.pk.pk